Creating Opportunities for Other Kids from Wyoming

By Lynnette Harris | March 16, 2022

Joe Crum is a paradox. A kid from a small Wyoming town who earned high school first-team all-conference honors in football, basketball, and track, but who doesn’t consider himself a “natural” athlete. The “little Crum” next to older brother Gary who played for the Miami Dolphins, but who worked up to bench pressing 475- 480 pounds in college. A guy who grew up a solid fan of University of Wyoming football and assumed he’d become a Cowboy and follow in his father and brother’s footsteps, but who took an offer to play at Utah State. Joe is so thoroughly an Aggie that he packed a U State flag from his home in Texas to adorn his Logan hotel room the weekend of November’s USU vs. Wyoming game — and hoped that his nephew, Wyoming’s 6’ 7” offensive tackle Frank Crum, would have a great game but that his teammates would not.

He’s a former player who sees a neurologist to address memory and cognition problems that stem from having had multiple, severe concussions but recalls details of games and individual plays and players from 40+ years ago. He’s a man who is proud of his commitment to outwork anyone in order to reach his goals yet sees God in the details of his life, even the disappointments.

He’s what some might call a gentle giant, but “gentle” isn’t likely to be how the guys who played football with and against him would describe him.

Joe was in high school when USU’s football staff stopped off in his hometown of Rawlins one Friday night before that weekend’s match-up between Utah State and the University of Wyoming. There wasn’t a lot to do in Rawlins, so USU’s coaches went to see that night’s high school game. The next week, USU assistant coach Terry Shea called to say that USU was interested in Joe.

“Several colleges offered me football scholarships,” Joe said. “My dad always told us that ‘Sports is a means to an end.’ He’d point out great players like Johnny Unitas and say, ‘He’s got to do something for the rest of his life after football,’ so I thought a lot about where I could get the education I wanted. I also wanted to go somewhere to make my own way and not be known as Gary’s little brother.”

Joe came to USU and set a very high bar for hard work that first semester, but he nearly lost his football scholarship when he simply dropped everything — including all his finals without notifying anyone — to comfort loved ones back home and be a pallbearer when one of his closest friends died in an industrial accident. When he returned to campus, Joe decided he had to get serious about his classes. He became the guy who sat in the front row of all his classes, went to tutoring sessions almost daily so his assignments didn’t get derailed when he didn’t understand something, studied hard, and trained even harder than before.

“I got a key to the weight room because coach was tired of me knocking on his door at night to get a key so I could go work out,” he said. “Me and my roommate, Clancy O’Hara, would work out about three nights a week during the season and watch Johnny Carson in the weight room on the little black and white TV with tinfoil on the antennae. That was always my thing: I will outwork you. I will out tough you. Therefore, you won’t have a chance.”

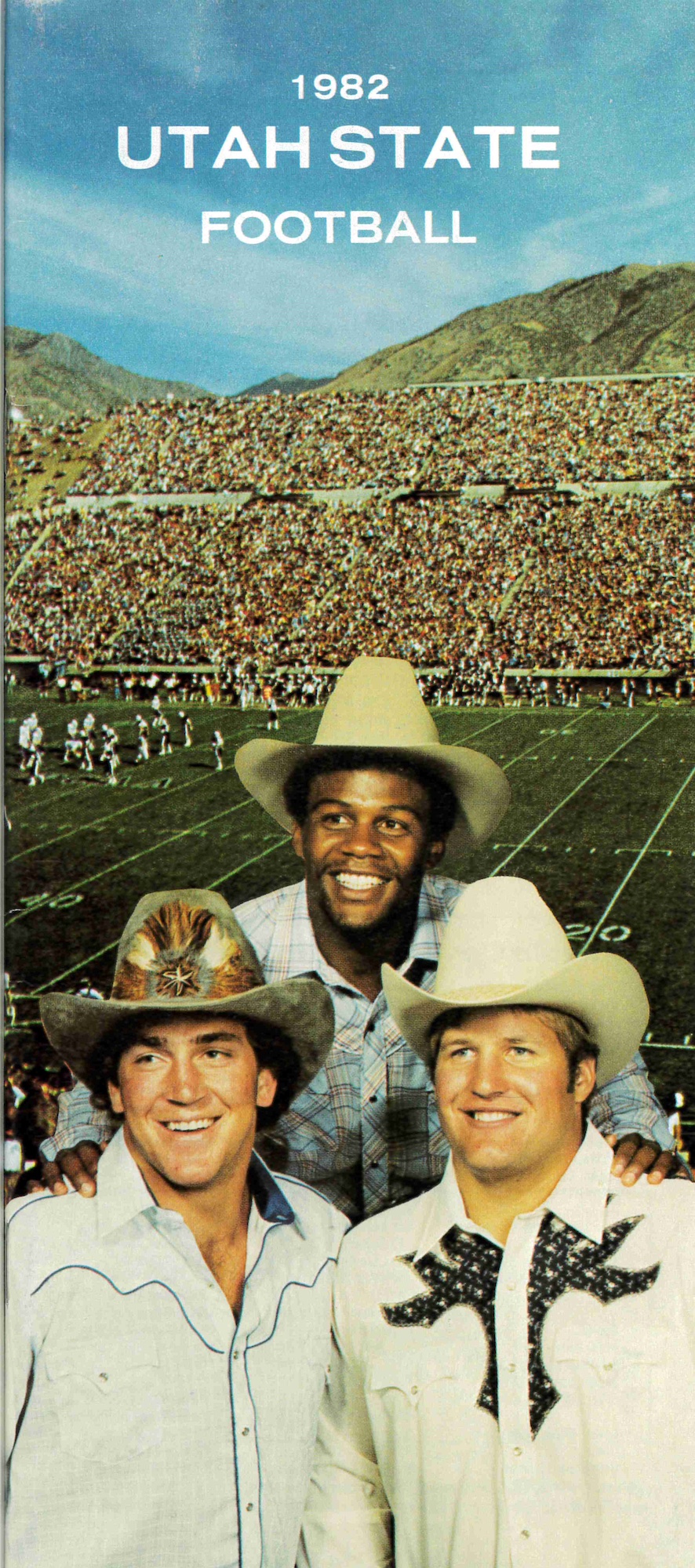

The description of Joe Crum in the 1982 USU Football Guide reads, “Capped a strong spring workout season with a selection by his teammates as one of USU’s ’82 tri-captains. Regarded as ‘dirt tough’ by coaches. Likely USU’s strongest football player, bench pressing 475-480 pounds. ‘His attitude is everything’ says line coach Rod Marinelli … exhibits outstanding work habits.”

Joe was named to the first-team all-league his junior and senior years and was expected to go in the first or second round of the NFL draft. On the roster of that all-West Coast team, he’s the only one of the 22 players listed who wasn’t selected in the first three rounds. That’s because on draft day he was in traction at a hospital in Salt Lake City due to serious back injuries.

“That was a blessing from God because I’d already had seven concussions, some that required a resuscitator and being in the hospital,” he said. “We just didn’t know the dangers then. One more might have been the end of it.”

Later, he was set to play for the United States Football League’s Pittsburgh Maulers. As he was working out in Logan to prepare for the rigors of pro training camp, news came that the league had folded. It was the afternoon of the last day to add or drop USU classes that quarter. Aggies of that generation remember that adding or dropping classes in the 1980s meant getting a paper form signed by professors and turning it into the registrar’s office by the end of the business day. Joe wasted no time, enrolled for the last eight credits he needed to graduate, and is thankful to this day that he didn’t play more football that would likely have caused additional brain injuries.

He earned a bachelor’s degree in finance with a minor in agricultural economics. After starting a career in banking (“but I’m not a suit-and-tie-every-day guy”), Joe worked for Purina Mills, where he helped to launch Purina Livestock Management Services and worked with cattle producers across the southern states. Later, he was with Treasure Valley Business Group, selling potatoes for fries in the U.S. and Mexico. He’s now been with Wilbur Ellis, a Texas-based company involved in agricultural research and agribusiness, since 2005. The experience has shown him even more of what’s possible for people working in agriculture.

“Ag has always been deep and dear to my heart,” Joe said. “I am interested in giving back to ag because it has long been my business. When I was a kid growing up, there just weren’t a lot of opportunities in Rawlins unless you wanted to go into the mining industry, or gas and oil, and those were very up and down. I didn’t want that. I wanted to go to college, and I knew athletics could be a way out.”

Joe is giving back to agriculture and people in and around his hometown by endowing a scholarship in the College of Agriculture and Applied Sciences. The endowment will grow and the scholarship will be available to graduates of Wyoming Indian, Rawlins, and Wind River high schools.

His early banking career experiences connected Joe with indigenous people living on the Wind River Reservation, and often with the pervasive poverty and poor living conditions there. More recently, his work with Wilbur-Ellis has included working with the Navajo Nation and its extensive, high-tech farming operations outside Farmington, New Mexico.

“I want to give opportunities to someone on the Wind River Reservation or from my high school to be able to attend Utah State, get a degree, and build a career in the ag sector,” he said. “Utah State came to my game on that Friday night and took a chance on an underweight kid from Wyoming. If they hadn’t, I would not have the kind of life I’ve had. I want to give young people from Wyoming who may be somewhat disadvantaged, or just don’t see what’s possible, the same kind of opportunities that I have had.”

Lynnette Harris

lynnette.harris@usu.edu